Women’s rights in ancient Egypt, although still extremely restrictive and demeaning, were still more progressive than those afforded to women in other ancient civilizations. What was considered privileges in ancient Egypt our now widely accepted as basic rights, but to the women of ancient Egypt being allowed to divorce, own property, or make a rape accusation was unique experience and assured that most lived comfortable lives. These rights elevated the quality of life that women had, however when it came to medicine, something that Egypt was renown for, this changed.

The Egyptians diagnosis and treatment of disease was extremely accurate. The Egyptians were the first to set a broken bone, come up with working theories on blood circulation, and were even able to suture surface wounds.

“Papyri show that the Egyptians had a good knowledge of bone structure, and had some understanding of breathing, the pulse, the brain and the liver.”

The BBC on ‘Ancient Egyptian Medicine: Knowledge about the Body and Surgery

These advancements meant that potentially fatal injuries in other ancient civilizations could be treated in ancient Egypt. Ancient civilizations from far and wide sought out ancient Egyptian doctors, who were renowned for their effective treatments.

“Although their understanding of physiology was limited, Egyptian physicians seem to have been quite successful in treating their patients & were highly regarded by other cultures.”

The Ancient History Encyclopedia

This was not entirely the case when in the field of women’s medicine however. Women’s health in ancient Egypt was impacted by misinformation and fear because of three common problems: incorrect theories about the womb led to harmful treatments, taboos around menstruation led to a double standard, and a fear of childbirth made the Egyptians turn to religion rather than science.

How Misinformation on the Womb Led to Inappropriate Treatments

In ancient Egypt, the womb was barely understood, yet many sought to control, rather than explore its many facets. Remedies such as amulets and spells were aimed at taming the womb rather than treating the underlying uterine ailments. Unable to explain the womb’s purpose, the Egyptians used loosely connected scientific theories to try to understand the workings of the womb. The two most influential theories were “Channel” theory and the idea of the Wandering Womb.

“The Egyptians developed a theory of physiology that saw the heart as the centre of a system of 46 tubes, or ‘channels’. “

The BBC on ‘Ancient Egyptian Medicine: Knowledge about the Body and Surgery

These ideas were not completely unreasonable, but were flawed to the point that misconceptions in multiple areas were created and negatively impacted women’s health and quality of life.

Despite having little to no proof, the ancient Egyptians believed the womb to be an organ capable of independent movement (wandering womb concept). Ancient Egyptian doctors concluded that uterine movement exerted pressure on internal organs, causing a variety of physical and mental disorders. This belief was the only logical conclusion of the time because anatomical dissection was not condoned by religion, and therefore more accurate observations could not be made.

“Internal surgery was not performed by swnw [Egyptian doctors]”

Lesley Smith on The Kahun Gynecological Papers

In a case from the Kahun Gynecological Papers, which details the medical treatment of women in ancient Egypt, a woman’s abdominal pain is explained as “disease of the womb through its movement.” These movements could supposedly be “controlled” through treatments, some of which were harmless like simple amulets, others, like the induction of uterine bleeding, were potentially dangerous. The Wandering Womb concept spread throughout the Middle East and was even apparent in western medicine until the sixteenth century. Erroneous beliefs about the womb stemmed from misconceptions about its workings, however this would lead to almost every ailment – those that could be explained and those that could not – being treated solely through the womb.

“In the middle of the flank of women lies the womb, a female viscus, closely resembling an animal, for it is moved of itself hinther and tither, […] and in a word, it is altogether erratic. It delights also in fragrant smells, and advances towards them; and it has an aversion to fetid smells, and flees from them; and, on the whole, the womb is like an animal within an animal.”

Plato on Hysteria

The idea of the wandering womb meant that almost any ailment could be explained as resulting from the womb’s movement. Channel theory also supported the idea that the womb was the root of all disease. The partially correct theory suggested that all parts of the body were connected through channels, and that in women these all led back to the womb, the root of disease. This helped support claims that diseases in unrelated parts of the body could be cured through only one organ, the womb. Poultices of varying herbs, honey, rancid milk, and alligator dung were all believed to heal different elements of the body when applied to the womb through the vagina. Fumigation, the smoking of herbs in or around the vagina, was a common remedy, and believed to “magically return the uterus to its normal position.”

“…by fumigating her with incense and fresh oil, fumigating her womb with it, and fumigating her eyes with goose leg fat. You should have her eat a fresh ass liver”

The Kahun Gynecological Papers

The induction of menstruation, or menorrhagia (excessive menstrual bleeding) was also thought to quell its movement, but menorrhagia, which is easily treated today, could lead to fainting, anemia, and infection in ancient times. Amulets and spells also attempted to control the womb. Surviving papyri mention spells to “stay the womb in its place” through prayer and the tying of amulets about the waist and thighs.

These remedies were not only ineffective but were responsible for complications like urinary tract infections and parasites. Foot, calf, tooth, head, and even eye aches were all said to come from the womb and were all treated as such. Prolapse of the genitals, a serious condition which requires surgical correction, was recognized by the Egyptians but was treated with simple poultices and prayer.

“prepare for her: oil too be soaked in too her vagina”

The Kahun Gynecological Papers

Had the ancient Egyptians not believed the womb to be all-encompassing, and in doing so created misinformed medical practices, the treatment of potentially serious conditions in women could have been greatly improved.

The ancient Egyptians desired not only to control the wombs movement, which was believed to be unnatural, but also its essential functions. Spells and amulets were used to influence the womb and to ensure a woman’s fertility or her continued pregnancy. Men would use them to prevent their wife from becoming pregnant with another man’s child. Spells to induce a miscarriage (the ancient day equivalent of an abortion) also existed and induced harmful menorrhagia. Rituals such as feeding seeds soaked in a woman’s vaginal juices to a frog or calling upon spirits of the dead were used on women to terminate a pregnancy or render a woman infertile. A plate from the third century depicts a spell performed under a full moon that allowed a magician to call upon spirits to block or unblock the channels that were believed to allow semen in and out of the womb. Although these spells rarely succeeded and were more often than not harmless, they show how the Egyptians sought to control the womb through multiple techniques.

The ancient Egyptians did not fully understand the womb but a greater focus on uterine exploration rather than taming could have allowed the medical profession to reach conclusions that benefited women. These misconceptions led to risky and ineffective treatments that potentially endangered the lives of countless women even centuries into the future. The womb was not the only part of women that was misunderstood, menstruation was similarly misinterpreted and this also had far-reaching effects.

A Fear of Menstruation Isolated Women and Created a Double Standard

With advancements in modern medicine, we now know that menstruation is a normal and natural phenomenon, however, to the ancient Egyptians, however, menstruation was both feared and respected. Papyri describing the supposed negative effects of menstrual blood contradict the Egyptian tenets about fertility and the gods. The bleeding associated with menstruation was feared by the ancient Egyptians, but the end results – fertility, a fetus, and even miscarriages, wielded power far beyond that of a menstruating woman.

The ancient Egyptians considered menstruation to be a form of purification, and because of this, menstruating women were feared. The ancient Egyptian word for menses was “hsmn”, which was interchangeable with purification. Blood, specifically, was believed to be the result of a “full body cleansing.” During their cycle women were considered impure (and in some cases evil), but after, they were thought to be cleansed. We know from annal temple records that menstruating women were not allowed to prepare food, or have sex, and anything they touched would be considered contaminated. menstrual blood was was believed to contaminate not only objects but also people. From these same texts, we know that if women did have skin to skin contact with a person or specific objects [such as a family member’s bed or utensils] that person or those objects would be considered “unclean for seven days and seven nights.” Menstruating women were not even allowed to touch their own children. This fear of menstruation was so extreme that in some places the women had to travel to secluded temples during their cycle.

A tablet of women who were journeying to a remote temple for their cycle, and were attacked along the way. Although all women survived, attacks such as these were relatively common. Menstruating women were isolated from society, and in some cases even sent on dangerous voyages.

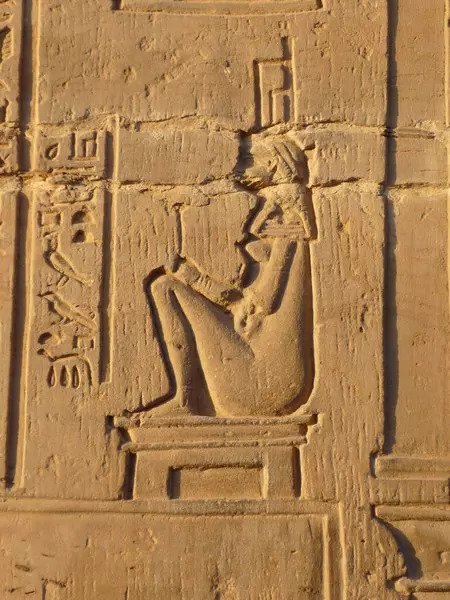

Although some women’s rights in ancient Egypt were advanced (women could divorce and choose their own husband), they were still considered inferior. However during menstruation this dynamic shifted. Records of workmen from the reign of Ramses II, tell us that when a woman in a man’s family was menstruating he should not work, and should “instead attend to her.” Furthermore, a partial text mentions that “he was not permitted… as she was hsmn,” which suggests that when women were menstruating they had some power over their male counterparts. Although menstruation did have negative connotations and was often misunderstood, the Egyptians saw its connection to life and birth, and menstruating women were even believed to have the power of Isis (one of the most powerful female gods in Egyptian mythology). This meant that menstruating women were both feared because of the association with impurity, and also respected because of the connection to Isis and fertility. Menstruation in ancient Egypt afforded women minor privileges, and although this does not excuse the hardships women were put through, this power shift is still worthy of mention.

The fear around menstruation in ancient Egypt created a double standard that allowed for the ostracization of women, while their blood was used for power over others. The blood of a menstruating virgin was believed to cure sagging breasts and thighs and coveted by magicians of the time. Ancient Egyptian farmers believed that a menstruating woman would kill their crops, but at the same time, they used the blood to ward off animals that would eat the harvest. Miscarriages meant the loss of a child and possibly the mother as well, and were reasonably feared, but the blood from a miscarriage was used in protection amulets and in many spells. Perhaps the most shocking belief related to female fertility was the power associated with the fetus. Reproduction in women was closely linked to the gods and spirits, and therefore a fetus was thought to have magical powers and a stronger connection to the gods. In extreme cases, ancient Egyptians desperate for power would kill a pregnant woman and steal her unborn child in order to commit crimes and wield its “magic.” When this happened the perpetrator was never punished as they were believed to have protection from the fetus’s malevolent spirit.

The ways in which menstruation was feared gave women and menstrual blood power, but this came at a cost. Women gained respect and power they did not normally have during their cycle, but were also isolated and restricted. The fear of menstruating women kept them from being included in society, while the fear of menstrual blood conveyed power and value and could result in attacks on women.

A Fear of Childbirth Meant that more Faith was put in Religion than Science

The taboos around menstruation may have put women in stressful situations, but pregnancy and childbirth were the most feared conditions for women. The Egyptians knew that childbirth was dangerous, however they relied more on religion than science to protect women during this process. Like many civilizations, ancient Egypt lacked knowledge about childbirth, but what tools they did have at hand were tossed aside in favor of the gods. When medicine and science was disregarded in a field that was already extremely dangerous, both mother and child were put in peril.

The Egyptians lack of information on gestation may have played a part in their dangerous pregnancies and childbirth. When texts from that period mention an “average pregnancy,” it is unclear if this was referring to how big the women’s abdomen was, the size of her breasts, or any of the other indicators of pregnancy. The Egyptians may have also not known how procreation worked. They were aware that “the womb is a vessel for sperm,” and that “the testicles carry life” but that is as close as they got to saying that intercourse led to pregnancy.

“it was believed that … the testicles were involved in procreation, but they thought the origin of semen was in the bones and that it simply passed through the testicles.”

Ancient Egyptian Family Life and Society

The Egyptians also believed that pomegranates and too much meat (protein) could lead to a “bad pregnancy.” However, we know now that pomegranates contain beneficial antioxidants and vitamins, and protein is an essential part of muscle building. Educated doctors, who were largely men, were absent from births as their presence would have been considered inappropriate, and were therefore not able to assist in birth or learn more on the childbearing process.

When the time came for childbirth and pregnancy, the ancient Egyptians did not use all of the tools they had to their advantage because of fears that made them turn to religion instead of science. A common problem of the time was breech births (when a baby is delivered feet or buttocks first), which can be addressed through the use of forceps. The first forceps were invented in Egypt in 180 BC but were only used for removing miscarriages or afterbirth. Birthing bricks (bricks used to create the optimal position for delivery), still used by some dulas today, were decorated with prayers to the gods, showing how even when they utilized medical principles, they still relied on religion.

Ancient papyri tell us that the Egyptians were extremely preoccupied with whether or not the pregnancy was its normal length. Although a premature or extended pregnancy can lead to deformation or difficult births, the Egyptians thought premature birth could summon malevolent spirits, and a late one could potentially “block the channels of the body” and affect the heart. “Spirits” were often employed to “block the channels” that the baby would be born through, in order to prevent a premature birth. Doctors of the time were capable of inducing labor but refrained from doing so until all paths such as prayer and spell had been tried. Gods and goddesses such as Taweret, associated with easy birth, fertility, and hippos, or Isis, were often invoked during long and painful labors that could have been eased through the use of medicines in addition to prayer. This reluctance to use the tools at hand during birth created complications and unnecessary risk.

It was not only birth that was difficult for women, but the recovery process was also very challenging. A tear in the vulva, a relatively commonplace injury after birth, would not have been treatable in ancient Egypt, instead prayer would have been the most “practical” course of action. Childbirth was the most common cause of death for women – and infants. The assessment of the neonate was also extremely crude. Newborns were exposed to the elements, often for extended periods of time, while their parents worked, and most illnesses, such as colic and whooping cough, would have been treated solely through prayer. We do not know the infant mortality rate in ancient Egypt, but most babies died before age three, and women before age thirty five – around the time of their fifth to seventh child. Prayer may have been effective for healing the soul, but during childbirth more decisive action would have been needed to save lives.

Childbirth today is much safer and easier because we are well informed on what a natural labor looks like, and because we have the tools to deal with almost any situation. This was not the case for the ancient Egyptians. The fear of childbirth meant that the ancient Egyptians relied primarily on religion for safe births, rather than science. Action, rather than prayer, would have been needed to save lives.

Conclusion

Despite their advanced medical system the ancient Egyptians feel prey to fear when it came to women’s health. Misinformation was common at the time as the tools needed to fully understand the body had not yet been invented, yet the ways in which fear changed how women were treated in ancient Egypt is clearly visible. The womb, an organ barely understood until the first anatomical dissections in Europe, was hypothesized over in ancient Egypt. The resulting ideas created fear that, in turn, led to the treatments of potentially serious diseases being not only ineffective, but possibly deadly. Taboos about menstruation, still seen today, created a double standard that excluded women from society but also gave menstrual blood extreme power that made women a target for violent attacks. Childbirth was feared within reason, but instead of using science to benefit women and infants the Egyptians believed that the gods offered superior protection during childbirth.

When all three of these problems in the field of women’s health were combined they made the field not only inaccurate, but capable of doing more harm than good. Had the Egyptians not lacked essential knowledge and harbored such a fear of the female body, which led to volatile remedies and abuse, the lives of countless women in ancient Egypt could have been greatly improved if not saved.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Primary

Plate 22, Walden & Co II, referenced in – Smith, Lesley. The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus: Ancient Egyptian Medicine. Tutbury, Staffordshire – UK, BMJ, 21 June 2017. Bio Medical Journal, pdfs.semanticscholar.org/fc44/fdb65cf46c2b6536228a83ed9b0b261899a1.pdf.

Accessed 17 Apr. 2019.

Relief of Women in a Boat, 595-550 B.C., The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/550890

Hatshepsut in a Devotional Attitude, 1479-1458 B.C., The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544446

The Holy Bible. Edited by International Bible Society, American Standard

Version, Grand Rapids, Michigan, Zondervan Publishing House, 1984.

McKay, William John Stewart. The History of Ancient Gynaecology. Part 1 ed., New

York, William Wood & Company, 1901.

Kom-Ombos Forceps, Ptolemaic Era 180 B.C., Science Museum London, http://broughttolife.sciencemuseum.org.uk/broughttolife/objects/display?id=92149

Secondary

Aubert, J. J., and Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. “Threatened Wombs:

Aspects of Ancient Uterine Magic.” Duke Library, Duke, 1989,

grbs.library.duke.edu/article/viewFile/3991/5563. Accessed 3 May 2019.

Brazier, Yvette, and Daniel Murrell. “What Was Ancient Egyptian Medicine Like?”

Medical News Today. Medical News Today, http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/

articles/323633.php. Accessed 18 Apr. 2019.

Drife, J. “The Start of Life: A History of Obstetrics.” Postgraduate Medical

Journal, vol. 78, no. 919, 2002, pp. 311-15. Postgraduate Medical

Journal, pmj.bmj.com/content/78/919/311. Accessed 7 Apr. 2019.

Frandsen, John Paul. “The Menstrual Taboo in Ancient Egypt.” Journal of near

Eastern Studies, vol. 66, no. 2, 2007, pp. 81-106.

Hasan, Izharul, et al. “History of Ancient Egyptian Obstetrics & Gynecology: A

Review.” Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology Research, Nov. 2011, pp.

35-39. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology Research Scholars Research

Library, file:///Users/smann23/Downloads/

5-Article%20Text-9-1-10-20170308.pdf. Accessed 7 Apr. 2019.

Historical Collections at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, University

of Virginia. “Ancient Gynecology.” University of Virginia, Historical

Collections at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library, 2007,

exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/antiqua/gynecology/. Accessed 5 Apr. 2019.

The Holy Bible. Edited by International Bible Society, American Standard

Version, Grand Rapids, Michigan, Zondervan Publishing House, 1984.

McKay, William John Stewart. The History of Ancient Gynaecology. Part 1 ed., New

York, William Wood & Company, 1901.

Moll, Michelle. “Magical Childbirth.” Archaeology of Ancient Egypt, 4 Aug. 2011,

anthropology.msu.edu/egyptian-archaeology/2011/08/04/magical-childbirth/.

Accessed 3 May 2019.

Nifosi, Ada. Becoming a Woman and Mother in Greco-Roman Egypt. Routledge, 2019.

Period. End of Sentence. Directed by Rayka Zehtabchi, produced by Melissa

Berton, Lisa Taback, and Garrett K. Schiff, Netflix, 2018.

R, Sullivan, and National Center for Biotechnology Information. “Divine and

Rational: The Reproductive Health of Women in Ancient Egypt.” National

Center for Biotechnology Information, 10 Oct. 1997, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

pubmed/9326756. Accessed 5 Apr. 2019.

Reeves, Carole. “Wandering Wombs and Wicked Water:.” Petrie Museum of Egyptian

Archaeology, edited by Alice Stevenson, UCL Press, 2015, pp. 54-55.

Characters and Collections. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1g69z2n.20.

Robins, Gay. Women in Ancient Egypt. Harvard University Press, 1993.

Smith, Lesley. The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus: Ancient Egyptian Medicine.

Tutbury, Staffordshire – UK, BMJ, 21 June 2017. Bio Medical Journal,

pdfs.semanticscholar.org/fc44/fdb65cf46c2b6536228a83ed9b0b261899a1.pdf.

Accessed 17 Apr. 2019.

Stockton, Richard. “Let It Bleed: A People’s History of Menstruation.” Ati,

version 1, revision 2, 9 Sept. 2016, allthatsinteresting.com/

menstruation-history. Accessed 3 May 2019.

Stulberg, Debra B., et al. “Obstetrician–Gynecologists, Religious

Institutions, and Conflicts Regarding Patient Care Policies.” National

Center for Biotechnology Information, NCBI, 28 Apr. 2012,

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3383370/. Accessed 7 Apr. 2019.

Teeter, Emily, and Douglas J. Brewer. “Ancient Egyptian Society and Family

Life.” The University of Chicago Library Digital Collections, Fathom

Archive, 1999, fathom.lib.uchicago.edu/2/21701778/. Accessed 25 Apr. 2019.

Todd, T. Wingate. “Egyptian Medicine: A Critical Study of Recent Claims.”

American Anthropologist, vol. 23, no. 4, 1921, pp. 460-70. JSTOR, JSTOR,

www.jstor.org/stable/660670. Accessed 18 Apr. 2019.

Tyldesley, Joyce. Daughters of Isis. Penguin Books, 1994.

Watterson, Barbera. Women in Ancient Egypt. Amberley Publishing, 2013.